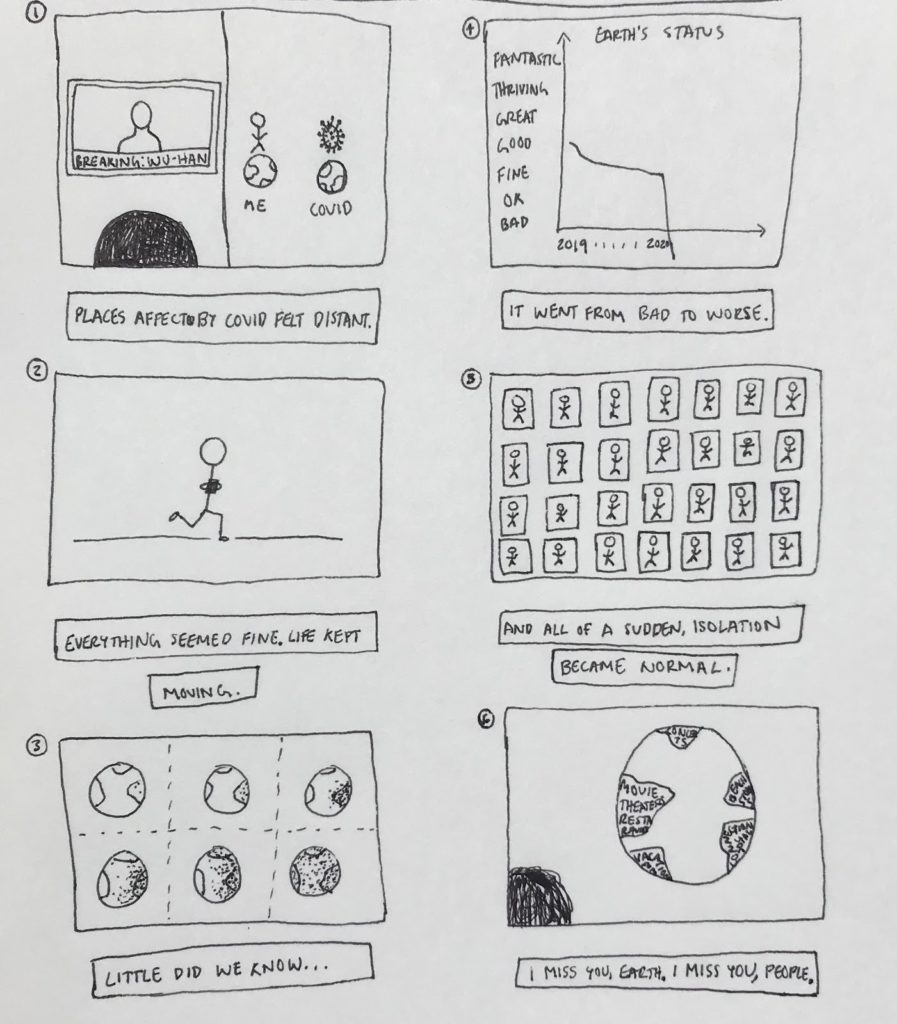

NEW YORK, NY— COVID-19 is rushing everyone into quarantine, isolation, and an influx in sales of medical equipment, to the point of making these difficult to access for medical workers. But prison inmates do not have this luxury of medical care, protective equipment, or even the possibility of quarantine. Around 0.7% of the United States’ population is incarcerated, but as of May 13th, 25,239 cases of the coronavirus were reported among inmates, approximately 1.82% of the 1,383,174 cases who had so far tested positive in the US. This elevated number is not only the result of the rapid spread of the pandemic, but also of the erosion of our prison system over the past 50 years.

In the past 40 years, the US’s prison population has increased by 500%, translating to approximately 2.3 million people incarcerated. This makes the US the country with the most incarcerated individuals, 25% of the world’s imprisoned population.

But these numbers come with a history and consequences. The main explanation for these numbers is the massive changes in sentencing policies and the invention of new crimes. In federal prisons, 47.3% of inmates are incarcerated on drug-related offenses. This is the result of sentencing policies from the War on Drugs era. In 1980, 40,900 individuals in state prisons, federal prisons, and jails were incarcerated for drug crimes, whereas in 2017, the number was 452,900. This increase is also the result of policies such as mandatory minimums, keeping drug-related offenders imprisoned for an average of 62 months in 2004 as opposed to 22 months in 1986. Most incarcerated for these charges have no prior criminal record for a violent offense and are not powerful actors in the drug trade.

Throughout this pandemic, jail and prison facilities have been called petri dishes for the virus, referring to the quick spread in close quarters and the demonstrated inability to contain an outbreak once a case was found. This is the case of the Cummins Unit in Arkansas. Situated in Lincoln County, the county with the most cases in the state (965), this facility’s number of cases was nearly a third of the state’s cases (approx. 600) by April 20th.

The outbreak in the Cummins Unit can be traced back to the lack of measures taken to minimize the number of cases. This is shown in the Frazier v. Kelley lawsuit filed by inmates of the Cummins Unit against representatives of the Arkansas Department of Corrections. In the complaint, it is brought to attention that “corrections officers and prisoners serving meals often do not properly use masks and gloves,” if these are used at all, that prisoners with symptoms are not immediately tested, but rather have to “wait days for a sick call,” and that prisoners are not held fully informed as to the plans of the Department to protect them from COVID-19.

All this adds up in the unprepared state the US was in at the beginning of the crisis; it is rendered significantly worse for the fact that even measures of social distancing cannot be taken in these conditions and that those who do test positive are kept in “punitive isolation conditions,” laying the blame and weight of the situation on the shoulders of those victim to the virus rather than on the department, and ultimately the system, that has placed them in this position. Prisoners interact with hundreds of people daily, from eating and sleeping together, sharing restroom facilities.

But clearly, one of the main problems leading up to this point, besides unpreparedness, is the overcrowding of prisons.

Overcrowding is not an inherently new problem. From the very first modern prison on Walnut Street in 1790, corrections facilities were seen as a solution to the cruelly applied death penalty and corporal punishment. The ultimate goal of this jail was not to keep people locked up forever, but rather to deter further breaches in the law. This is similar to the ideals which we imagine are applied in our current prison system: prisons are places of reform and correction in which the final result is reintegration of the convicted person into society. However, in Walnut Street, which had solitary confinement cells as well as a larger room in which less dangerous inmates were set to work, the larger room quickly got overcrowded, leading to a dirty, unsanitary and unsafe space for prisoners. This was a step closer to the European prisons at the time, which the Walnut Street jail was specifically trying to avoid. While this problem has persisted through the centuries, it exploded during the years of “tough on crime” policies during the War on Drugs. Harsher sentences for low-level drug offenses pushed the number of individuals incarcerated for drug crimes from 40,900 in 1980 to 452,900 in 2017. Also, the average time in prison for federal drug offenses shot up from 22 months in 1980 to 62 months in 2017. These changes have shaped our country’s corrections system ever since. With the constant overflow of people convicted and the length of their sentences, it is practically impossible for facilities to contain everyone safely. These conditions lead to overcrowding, unsanitary living conditions, and higher assault rates.

Beyond overcrowding, inmates do not typically have access to protection services, making them silent victims of physical mistreatment, inadequate medical and mental health care and barely tolerable physical conditions. Prisoners are victims of harassment and abuse often from corrections officers as well as fellow inmates.

In a plea to President Trump, dozens of experts pressed on the urgency of making quick decisions to protect immigration detainees and inmates. Attorney General William P. Barr stated that officials were working on expanding home confinement, rather than to directly release federal prisoners. In order to qualify for home confinement, inmates were assessed based on age and vulnerability to the virus, the security level of their current facility, prioritizing inmates in lower security facilities, their conduct in prison, whether or not the inmate has a “demonstrated and verifiable re-entry plan that will prevent recidivism,” and the crime committed by the inmate. Yet amid this list of seemingly reasonable criteria is the doubt of how many people these guidelines apply to and what effect this will ultimately have on the spread and the health of vulnerable or at-risk inmates. Along with this, some prosecutors and members of the government directly implicated in this problem refuse to waive restrictions such as the 30 day waiting period for approval of an appeal for compassionate release. In normal circumstances, this waiting period is for the warden to gather information about the appeal and the inmate appealing, and make a decision as to whether or not compassionate release should be granted. However, in the setting of a pandemic, these regulations do more harm than good. They delay the decision which could be crucial for a prisoner’s health and safety. Additionally, due to the length of the incubation period for this virus, continued exposure could lead both to a deterioration in the health of the inmate as well as a possible spread once the appeal is granted.

While bail is unquestionably one of the most complicated parts of our prison system, the standard it creates is not. Typically, prisoners who are offered bail have a bail price in accordance with both the severity of the crime committed as well as what is financially possible or appropriate for the inmate and their family. This said, the system of bail creates both opportunity for those in measure to pay the price as well as a culture prioritizing money and good connections over inmates who are ready to reintegrate back into society.

Meanwhile, Michael Cohen and Paul Manafort were recently released despite the fact that federal officials have often stated that 50% of the inmate’s sentence must be completed to qualify for early release; Cohen had served only a third of his 3-year sentence while Manafort had served less than a third of his sentence. While policies for who qualifies for release keep changing, this is an inconsistency with cases like Eddie Brown’s in Tennessee. Brown is incarcerated for selling meth and has completed 6 years of his 15-year sentence. Brown is 47 and has hepatitis C. Having earned a welding certificate, being trusted to drive other prisoners to the factory he works at as chief welder, and having completed a 500-hour substance abuse program, one might think that Brown would qualify for compassionate release, but the story of affording a lawyer has not even begun. If laws and regulations keep shifting who can be released or placed in home-confinement, they have not changed in pushing down prisoners who cannot afford to protect and defend themselves. Additionally, while no time-served threshold was referred to in U.S. Attorney General William Barr’s memos on the subject, these have been widely used to deny certain at-risk inmates compassionate release or even home-confinement. In contrast, Manafort and Cohen were able to afford lawyers to defend their cases.

Another factor putting privilege over merit is the use of the “risk assessment” algorithm called PATTERN. PATTERN is a system that predicts the probability of recidivism of a current prisoner or defendant based on a series of factors and assigns a pointage to said person, with a lower pointage signifying a lower-risk person. It was created in 2018 as part of the First Step Act signed by President Trump to help reduce federal prison population. In the context of the pandemic, Barr instructed the prison system to prioritize the release of prisoners with low scores. While the concept of more precise estimations as are made loosely by judges currently seems appealing, PATTERN has only been in use since the beginning of the pandemic and relies on wildly unfair factors relating to socioeconomic factors. These factors are anything from marital status to education to finances and neighborhood. Advocates for PATTERN and similar rating systems emphasize the scientific factor which such algorithms give predicting recidivism but forego that these programs are only another part of the US prison system for people of low-economic standing and people of color.

Indeed, while PATTERN seems to promise some form of the exactitude which we have come to associate with algorithms and computers, it is relying on factors which disproportionately affect people of color. Using this system, only 7% of black men in federal prisons would qualify as low-risk enough to be released using PATTERN, as opposed to 30% of white men. This disbalance is not the result of one faulty algorithm, but rather of an entire system that has, throughout its history, been designed to trap people of color. As of 2017, more than 60% of the US prison population is made up of people of color. This is especially visible in that, as of 2017, the lifetime likelihood of imprisonment of men born in 2001 was 1 in 3 for black men compared to 1 in 17 for white men. These racial disparities were only heightened by the War on Drugs and the era of “tough on crime” policies. In this time, there was a racially coded myth of the “Superpredator,” “radically impulsive, brutally remorseless” “elementary school youngsters who pack guns instead of lunches.” This myth led to nearly every state expanding laws exposing children to adult sentences, including life without parole. Professor at Princeton John Dilulio and criminologist James Fox predicted a rise of these predators by 2010. This prediction, however, turned out to be completely wrong as rates of crimes in youth fell in the mid-1990’s. Although this scare availed to nothing, it set up laws and treatment that crushed young offenders and set a lasting stereotype. Another example of discrimination from the same period that still shapes our prison sytem today is the gap in drug enforcement and sentencing. When President Richard Nixon started the “war on drugs” in 1971, its objective was the criminalization of black people. During the crack crisis of the 80’s this served to generate stories of violent “crack babies” and fuel the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986. Congress inflated prisons’ and law enforcement’s budget by millions in order to contain those found guilty following this act. Following this, from 1991 to 2001, nine times as many black people were incarcerated in federal prisons for crack offenses as white people. Though the views of addiction and substance abuse have softened over the past decade, the racial injustices are still seen in the more recent opioid epidemic. Associate professor Helena Hansen in the Department of Psychiatry at New York University remarked that: “When the articles mentioned black and Latino opioid users, it was a crime report, their criminal history, etc.” In 2016, black people were arrested twice as much as white people for cocaine, found the USA TODAY NETWORK. The history of the US’s racism is blatantly apparent in its prison system and how the foundations of this system have strived to crush people of color from the very beginning.

The 13th amendment has a loophole. This is in the phrase “except as a punishment for crime,” an exception to the rest of the amendment: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”From this loophole begins the rabbithole of prisoner’s exploitation. Many people loosely believe that prisoners should work as part of their sentence, but what isn’t always as visible is how much large corporations and parts of our government lean on this labor. This is the case of the New York State Clean hand sanitizer, produced in view of price-gouging and shortage. The unveiling of the hand sanitizer took place on March 9th at a briefing at which Governor Andrew Cuomo explained that this product was “made conveniently by the state of New York.” While he goes on to mention that the producers of this hand sanitizer is Corcraft and mentions some other products “manufactured” by Corcraft, he conveniently leaves out that Corcraft is in fact a part of the Department of Correctional Services, Division of Industries that is powered by inmates. While Corcraft Products sport a bright logo and the mission statement “employ[ing] inmates in substantive jobs that help teach a good work ethic and valuable work skills, to help offset the cost of incarceration, to help reduce disruption in the prison environment and to meet expectations of New York State’s citizens,” its emphasis is more on meeting the “expectation of New York State’s citizens.” This is at the cost of inmates who have worked at wages as low as 16 cents per hour and an average of 65 cents per hour. While the New York State bill A01275 or “Prison Minimum Wage Act” was introduced in January of 2019, the current progress of this bill is only at 25% and it seems unlikely to pass during this pandemic. In such, prisoners work for small sums of money at the profit of both corporations and the state. This is in line with the loophole in the 13th amendment, but not with the social and legal reforms brought on by the amendment itself. Another touch of cruelty in this wildly flawed system is the fact that as of today, prison inmates in New York State are prohibited from using or receiving hand sanitizer as it is alcohol-based. It is considered contraband. And while it is tempting to dismiss this as a miscalculation, it is only further proof of the cruelty and brokenness of our current prison system and the dire need of reform. If any other 1% of our population was exposed to such harm on a daily basis, we would not stand for it. So why should we for prisoners?